Daniel Fincke of the blog Camels with Hammers has a post defending the relevance of philosophy. It includes a list of philosophical questions which Finke claims “Everybody cares (or should care) about.” After giving his list, Fincke says:

Daniel Fincke of the blog Camels with Hammers has a post defending the relevance of philosophy. It includes a list of philosophical questions which Finke claims “Everybody cares (or should care) about.” After giving his list, Fincke says:

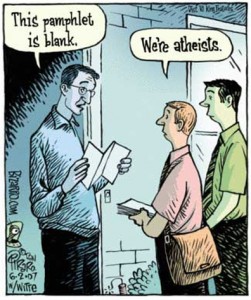

The frequency with which I see these and numerous other philosophical questions discussed all over the place, on a daily basis, is staggering. And without such questions, atheism blogs would altogether cease to exist as such. No one enthusiastically visiting Freethought Blogs or, even, Why Evolution Is True can say they find philosophy irrelevant with any self-awareness or internal coherence.

Fincke would be correct if his point were that atheist blogs couldn’t exist if they were prohibited from ever talking about anything within the board topics philosophers have traditionally claimed for themselves. Because, ya know, the existence of God is generally considered a philosophical topic. But he’s mistaken insofar as the specific questions philosophy professors care about tend to be very different from the questions someone like Jerry Coyne is going to care about.

Take for example the first question on Fincke’s list: “what are the differences between knowledge, opinion, and faith?” This is a very hard question to answer with perfect precision, if you approach it the way many philosophy professors do, asking what the necessary and sufficient conditions being knowledge, etc. are. But most people, even though they can’t give a perfectly precise definition of “knowledge,” still have a concept of knowledge they successfully apply in most cases. We care about knowledge, but we can get by fine without a philosophical theory of knowledge.

If we have trouble telling the difference between knowledge and nonsense, it’s usually due to lack of specific information relevant to the subject, not due to lack of philosophy. Or, it’s because people are refusing to evaluate their own religious beliefs the way they would others’ religious beliefs. We don’t need philosophy to figure out that many of the claims Mormonism or Scientology makes are nonsense. And the same goes for more mainstream religions.

Another thing: I used to think that the number one thing non-philosophers need to know about philosophy is that philosophers are unable to agree with each other about anything. Now I think it’s something even more fundamental: the fact that philosophy isn’t very much like science at all. I say that because of this:

At certain points physics and biology and mathematics, etc. all become virtually inaccessible to anyone but specialists too. So why exactly would anyone expect epistemology or ethics or philosophy of mind or metaphysics, etc. to remain accessible to everyone when being analyzed in the most rigorous and advanced ways? That’s the way it has to be if we are to get beyond a simplistic grasp of issues and into their deeper intricacies. If you do not personally care about all the details of a subject, since you are happy trusting credible authorities who have thought through them for you, then that’s fine. It’s inevitable we each have to do this in most cases since it is literally impossible, given the current state of the normal human brain, to assimilate all the knowledge required to have a specialized opinion on every topic.

I don’t understand how Fincke could say the bit about “trusting credible authorities.” Even if you think philosophy professors are “credible authorities,” then you’re going to have to have the problem of there being many credible authorities on both sides of any given philosophical question. But more broadly, it should be obvious that science and philosophy are really, really different, so it isn’t obvious that say, because the esoteric stuff scientists do is often necessary, therefore the esoteric stuff philosophers do must also make sense.

More generally, philosophers shouldn’t expect to be treated with the same deference scientists are, because philosophy doesn’t have science’s accomplishments. A lot of scientists seem to have trouble with that fairly obvious point.

‘Verbose Stoic explains why Coyne is missing the point. In short, it does not matter whether there actually is a God.’

‘So he quite likely does care about the question of whether or not there is a God. Examining that question adequately involves, in part, developing a coherent account of what we mean (or could mean) by God.’

So theology is a useful subject because it simply does not matter where or not there is a god.

And why is it useful?

Because studying theology helps us answer the question of whether or not Yahweh exists.

Why should people care whether or not Zeus took on the foreknowledge a swan had when he took the shape of a swan?

Why is that a useful subject for a philosopher to study?

Oh sorry I forgot. Those gods are childish nonsense, hardly worth being studied by a Real Academic, unlike the god that was carried around in a box by Israelites wandering in a desert – a subject of study which is so serious that anybody who does not do is not fit to call himself a scientist.

‘Is your own life rightfully yours to end or does society have a right to prevent your from hurting yourself when you are depressed but in all other respects physically healthy enough to live painlessly? Is abortion good or bad? Or under what circumstances is abortion good or bad? ‘

Gosh. I had no idea that philosophers were the go to guys to answer these questions.

In my ignorance I had rather assumed that philosophers had not come to any conclusions that were not disputed

.

Uh, have you ever heard of computers? They are kind of a big deal. And before you say that they were invented by Mathematicians and Engineers, please look up the actual history. By far the most important figures were Frege, Russell, Hilbert, Godel, Turing, Church, von Neumann, and (to a lesser extent) Wittgenstein. Several people on that list (including the most important ones) were uncontroversially Philosophers, and ALL of them at least dabbled in the subject (i.e. talked with Philosophers and/or published in Philosophical journals).

Also, I don’t think it’s true that Philosophers don’t agree on anything. The story usually goes that as soon as most Philosophers start agreeing, a new science is born. Obviously that is too simplistic, but it seems true about many cases. Most recently, Linguistics, Computer Science, Psychology, Economics and possibly Cognitive Science all arguably emerged from Philosophy. At the very least, they cite Philosophers as founders of their fields (I’m talking Frege, Montague, etc. in Linguistics, Keynes, Smith, etc. in Economics, etc. etc.).

To clarify: the most important figure in the history of computation in the past 200 years was arguably Frege, and he is also considered the founder of contemporary analytic Philosophy. I’d go so far as to say that he was also the most important Mathematician of the past 150 years or so. This was not a coincidence.

When I talk about philosophy, I’m generally using it in a sense that excludes work done using empirical methods, or the methods of mathematics. Of course people who we call philosophers have done good work of both sorts. I still think my comments apply to those areas where we don’t know how to use either sort of method to answer our questions.

I don’t think the “historically, philosophers have had accomplishments which then became science” defense goes very far in defense of modern philosophy.

We can actually look at modern philosophy, and make judgment calls.

We’re not restricted to just assuming that because the label “philosopher” once applied to people who accomplished useful things, that people using that same label will continue to accomplish useful things.

I’ve also questioned the deference philosophers get within religious circles. In my (admittedly limited) experience, philosophy is most often used as a smokescreen–”We can’t discuss the epistemology of that issue until we’ve agreed on the ontology” and so on.

Science delivers (as evidence, consider the science behind the technology of computers and the internet), but what has philosophy done that’s comparable?

‘Uh, have you ever heard of computers? They are kind of a big deal. ‘

I see

The philosophy of religion is useful, not because it matters whether god exists or not, but because it leads to the invention of computers.

Chris: Fair enough, but “the methods of mathematics” seems to be smuggling in far too much of what is, both currently and historically, considered philosophy. And actually, if you want to try to define “the methods of mathematics” more narrowly, you’re going to lose the invention of computers as discovered by the application of such methods. Turing’s original paper giving what he convinced nearly everyone was the correct formal analysis of our intuitive notion of an algorithm (i.e. the Turing Machine) was just that: straight-up conceptual analysis of an intuitive notion (now, I fully agree that this almost never works, and probably isn’t the best methodology in Philosophy). This plus the definition of a Universal Turing Machine (same paper) lead directly to the invention of computers. It was very much top-down. Also, it wasn’t at all motivated by a desire to invent an extremely useful machine; the motivation was entirely from the Foundations/Philosophy of Mathematics.

So, if you consider such methods not philosophy, and you consider, say, the work in semantics prior to the proper beginnings of linguistics as a science too empirical or too mathematical to be philosophy, then it seems you’re almost ruling out the possibility of any scientific progress in virtue of philosophy by definition. Here’s an unfair caricature: “Philosophers have never done anything!” “What about all these Philosophers who did uncontroversially important things?” “Well, sure, but they weren’t doing Philosophy then, they were doing Math or Science.” But what makes a method mathematical or scientific? Not being philosophical? What about the people who reflected on the conceptual apparatus and proper methodology for the study of, say, language? If that isn’t philosophy, I’m having trouble seeing what is, besides “methods you don’t like”.

I mean, I definitely don’t like many of the methods used in Contemporary Philosophy (especially in Ethics, Philosophy of Religion, etc.), but I think the majority of living Philosophers agree that these methods are problematic (well, at least a bunch of them). I certainly agree with you that Philosophers need to study more science, but I also think that Scientists need to study more philosophy. Look no further than Quantum Mechanics if you want to see what happens when scientists decide not to bother with foundational questions they consider to be “too philosophical”. Many, many Physicists in the past couple decades have begrudgingly accepted that that was a bad idea. Bell’s Theorem finally brought many of them around.

Patrick: There is no need to speculate about this; it’s an empirical question. Look it up. Read up on the history of the more recent sciences. Several of these founding figures are still alive (well, barely).

Nate- The “its an empirical question” defense is a lousy way to defend the claim that philosophy often becomes science. Because once philosophy becomes science, it ceases to be philosophy.

Little Boy: The emperor is naked!

Royal Tailor: Silly boy! Empirically, the emperor has removed a great many clothes! What makes you so certain he has no more clothes to remove?

Little Boy: Non empirical evidence?

Patrick: I wasn’t trying to escape the question by calling it not philosophically relevant; I was trying to semi-politely say that you don’t know what you’re talking about.

Yes, once Philosophy becomes Science, it ceases to be Philosophy. What’s your point? Doesn’t this make Philosophy extremely important?

Anyway, name the science and I’ll cite particular examples.

No, it makes past-tense philosophy extremely important. The distinction is relevant.

I made the point rationally the first time, comically the second, and now, in keeping with your tone, I’ll make it in a derogatory fashion:

If you would pretend to know the first thing about philosophy, you shouldn’t be basing your entire argument around an erroneous instance of induction.

Patrick: I’m not sure if you misunderstood me or you’re trolling or what. Oh well.

Let me see if I understand you. So you’re saying that, sure, Philosophy in the past has been important, but we can’t rationally conclude from that that Philosophy will continue to be important, since that would be an “erroneous instance of induction”. Umm, ok. What counts as the past? 100 years ago? Last week? If you want to be a radical skeptic, then fine, you can say that even if Philosophy made contributions last week, we shouldn’t conclude that it will continue to do so. The problem, of course, is that at that point you’re committed to saying the same thing about the sciences, our confidence that the sun will rise tomorrow, etc. etc. Citing radical skepticism to defend your position is pretty much always a bad idea. If you think you don’t need to, then please explain why Philosophy making amazing contributions up until recently shouldn’t lead us to conclude that it is still doing so.

Let me put it this way: we have to make certain assumptions in order to be able to do or say anything at all. Play the radical skepticism card and you’ve given up the game, at which point Philosophy can no more be defended than absolutely any human endeavor whatsoever.

Again, if you truly want to know what contributions Philosophy has made in the past century or 50 years or whatever, then either look up the relevant history of science or ask me and I’ll point you in the direction of the relevant articles. Just stop pretending you know what you’re talking about.