A good chunk of my blogging over the next few weeks will be following up my post on leaving philosophy for neuroscience, particularly my comment about the worthwhileness of philosophy. Among other things, I’m planning on doing a (likely multi-part) review of Gary Gutting’s book What Philosophers Know, which I had mentioned in the previous post, and a post on how I’ve bought in to bad philosophical arguments in the past.

A good chunk of my blogging over the next few weeks will be following up my post on leaving philosophy for neuroscience, particularly my comment about the worthwhileness of philosophy. Among other things, I’m planning on doing a (likely multi-part) review of Gary Gutting’s book What Philosophers Know, which I had mentioned in the previous post, and a post on how I’ve bought in to bad philosophical arguments in the past.

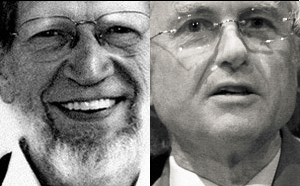

I’ve decided to start off with something simple though: the scientific ignorance of some philosophers, and the philosophical ignorance of some scientists, and why I think the former is much worse than the latter. I’ll focus on two famous cases: Alvin Plantinga and Richard Dawkins.

I’ve written about the allegations of ignorance against Dawkins here. To put it briefly, while Dawkins certainly isn’t an expert in philosophy or theology, the attempts to dismiss him on these grounds are simply absurd. It’s silly to complain that he doesn’t cover everything, and as far as I can tell, the allegations that he’s misrepresenting the people he’s attacking themselves depend on misrepresenting Dawkins.

Also, as Dawkins puts, theology isn’t a subject. It has failed to produce a body of results in the way that, say, chemistry and physics have. It makes sense to criticize someone for being ignorant of scientific facts; it makes no sense to criticize someone for being ignorant of theological facts. It makes sense to criticize someone for ignoring the best evidence for a scientific theory; it makes less sense to criticize someone for ignoring the best evidence for the existence of God, because the experts can’t even agree on whether there is any good evidence, much less on which evidence is the best.

Now if you want an example of someone who really does deserve to be criticized for the things they’ve said

on a subject they’re ignorant of, it’s hard to think of a better example than Alvin Plantinga writing on evolution. Well, just about any anti-evolutionist would do, but Plantinga is an interesting case because he is aware of his own ignorance, but uses superficially humble declarations of ignorance as a cloak for philosophical self-importance:

If the question is simple, the answer is enormously difficult. To think about it properly, one must obviously know a great deal of science. On the other hand, the question crucially involves both philosophy and theology: one must have a serious and penetrating grasp of the relevant theological and philosophical issues. And who among us can fill a bill like that? Certainly I can’t. (And that, as my colleague Ralph McInerny once said in another connection, is no idle boast.) The scientists among us don’t ordinarily have a sufficient grasp of the relevant philosophy and theology; the philosophers and theologians don’t know enough science; consequently, hardly anyone is qualified to speak here with real authority.

The implied assumption of this paragraph is that while it may be problematic for non-scientists to spout off about science, but its just as bad for non-philosophers to talk about topics philosophers have declared to be theirs. So really, it isn’t actually that bad for philosophers to spout off about science.

But a quick read Plantinga’s discussion of science brings up howlers beyond anything Dawkins has been accused of. Plantinga complains, for example, about “the nearly complete absence, in the fossil record, of intermediates between such major divisions as, say, reptiles and birds, or fish and reptiles, or reptiles and mammals” (wrong) and implies that the evolution of the eye is absurdly improbable (also wrong).

It’s hard not to see Plantinga’s essay as a bit dishonest: He quotes Gould on the lack of transitional forms, but ignores Gould’s complaints about how his words on the subject had been twisted (in spite of quoting a different section of the Gould’s “Evolution as Fact and Theory,” where Gould lodges that complaint.) He also uses the infamous Darwin quote on the apparent absurdity of the evolution of the eye, while ignoring Darwin’s proposal for how the eye evolved.

However, I still think that on the whole, Plantinga’s statements on evolution are probably the result of ignorance. I suppose some creationist tract told him that bird-reptile transitions were lacking, and therefore he assumed that Gould’s complaints about having his words twisted must have been hairsplitting. Here, ignorance isn’t really much of an excuse–the mistake could have been avoided if Plantinga had bothered to go ask a qualified paleontologist, “is this right?” Still, I think Plantinga is a fine example of the consequences of scientific ignorance. And they’re far worse, far less excusable, than the consequences of philosophical ignorance or theological ignorance as seen in someone like Dawkins.

Now it may be that there are worse examples of philosophical ignorance to be found than Dawkins. (Any suggestions?) However, it’s not clear what such an example would even look like. True, it’s possible to be clearly wrong about what some philosopher has said, but such mistakes rarely (if ever) put one at risk of mistakenly rejecting a well-established philosophical finding, because philosophy doesn’t have much in the way of findings.

Another point: When I’ve talked with friends about Plantinga’s (and some other philosophers’) statements about evolution, they’re always surprised. They expect being a philosopher to make people generally reasonable. I’ve never been surprised in this way, though I guess I should be. In the past I’ve bought in to the idea that studying philosophy brings with it a kind of general-purpose rationality. Now I think that was a mistake. Philosophy at best makes people more rational in some ways, while being useless in many other ways. It may even make people more likely to say foolish things on certain subjects, if they mistake their ignorance for philosophical insight.

I still don’t quite see why you think scientific ignorance is somehow less serious than philosophical ignorance. Of course philosophical ignorance cannot be understood on the model of scientific ignorance — we can’t understand the phenomenon as someone’s simply being unaware of the relevant philosophical facts. (Some philosophers might push you on that, but I for one am more than happy to grant it)

The point is this: if one is involved in establishing the truth of a claim like “God almost certainly doesn’t exist,” or “Morality is based on the well-being of conscious creatures” (to take another example of philosophical ignorance — Harris’ “The Moral Landscape,” which I admittedly haven’t read but have heard talk about), one is entering an at least partly philosophical fray, whether one likes it or not. One is entering into a debate in which empirical findings may well be relevant but are not sufficient to determine the answers. One must be philosophically competent to argue for such claims reasonably and responsibly. If one remains ignorant, then one simply hasn’t established the claims one set out to.

Is that serious? Well, it sounds pretty serious to me, but then I’m a philosopher. But why don’t the two following claims both hold? — Plantinga’s arguments are bad, because the scientist (and hence, all of us) have reason to reject them. Dawkins arguments are bad, because the philosopher (and hence, all of us) have reason to reject them.

>One must be philosophically competent to argue for such claims reasonably and responsibly.

What does “philosophically competent” mean here? If it means “having studied philosophy extensively,” I think this claim is obviously false. What on Earth would make it impossible for a non-philosopher to argue reasonably and responsibly against the existence of God?

Maybe you think there are powerful arguments for the existence of God than any responsible participant in the discussion must address. However, I think that even most of the arguments given by “sophisticated” defenders of religion have been pretty terrible.

Even if I’m not entirely happy with the selection of arguments Dawkins chose to address in TGD, I can’t see that there are clearly much better arguments he could have addressed there.

I’ve not read most of Dawkins’ book, and what I have read I read four years ago. But I do remember his basic argument for the non-existence of God relying on the assumption that God is massively complex. But this is of course massively question-begging, at least for a vast range of intelligent theists, who think of God as simple. Part of the interest and mystery involved in philosophical theology is in determining how a being which is essentially simple can have personal attributes, powers of various sorts, and so on. Don’t get me wrong — I don’t think this stuff ends up anywhere useful, ultimately, but the reason isn’t just because God would obviously have to be complex. That’s at least a claim that needs some supporting argument, which will require some level of philosophical competence.

I don’t have a ready definition for “philosophically competent,” but it certainly need not mean “being a philosopher” in the modern institutional sense, or anything like that. One can be a “non-philosopher” and argue convincingly about the existence of God, surely, but one can’t do so without doing good philosophy. But perhaps this is what you disagree with? What sorts of questions are “Is there a God?” and “On what is morality based?” if they are not philosophical? Are they empirical questions? Are they pseudo-questions? Is philosophical ignorance not a serious problem because there is no such thing as a philosophical question?

I addressed the complaint about God being simple in my previous post on Dawkins – his discussion may not be very thorough, but he isn’t ignorant of the fact that many theologians have claimed God is simple.

God and morality are philosophical subjects insofar as some of the people that call “philosophers” today are in the business of discussing them, and other academics aren’t so much in the business of discussing them. But it’s not obvious that anything deeper follows from that sociological fact.

In particular, it isn’t clear why it would take more philosophical competence to responsibly say that “there almost certainly is no God” than to say “there almost certainly aren’t any fairies.”

In the case of the morality question, it seems (to me) more plausible that the question is somehow special, but that doesn’t mean that what philosophers have had to say about it has been generally valuable. In a footnote to his new book, Harris mentions that he actually has read a great deal of what philosophers have had to say about morality, but decided against discussing it in his book.