Most religious believers in the U.S. are not Rick Warren. Most religious believers in the U.S. are not William Lane Craig. In some ways, this is not obvious from the statistics: surveys regularly report things like “half of Americans are creationists,” or “half of Americans accept Biblical inerrancy.” But in spite of these statistics, the Barna Group insists that only 9% of Americans have a “Biblical worldview.” Why? Because while you might find between a quarter and a half of Americans agreeing to any particular bit of Christian doctrine, the portion that accepts a particular bundle of several doctrines will necessarily be less than the portion that accepts any one doctrine in the bundle. Leaders like Warren and Craig tend to be people who’ve signed on to some fairly standard bundle of Christian beliefs. This doesn’t, however, mean that they can get their followers to sign onto those same bundles in their entirety.

Most religious believers in the U.S. are not Rick Warren. Most religious believers in the U.S. are not William Lane Craig. In some ways, this is not obvious from the statistics: surveys regularly report things like “half of Americans are creationists,” or “half of Americans accept Biblical inerrancy.” But in spite of these statistics, the Barna Group insists that only 9% of Americans have a “Biblical worldview.” Why? Because while you might find between a quarter and a half of Americans agreeing to any particular bit of Christian doctrine, the portion that accepts a particular bundle of several doctrines will necessarily be less than the portion that accepts any one doctrine in the bundle. Leaders like Warren and Craig tend to be people who’ve signed on to some fairly standard bundle of Christian beliefs. This doesn’t, however, mean that they can get their followers to sign onto those same bundles in their entirety.

Some Christians who lack Barna’s “Biblical worldview” have thought long and hard about all of the more controversial Christian doctrines, and only then made up their minds about which ones they can accept and which ones they have to modify. But I suspect most of them aren’t like that. Rather, they hear some things and say they believe them because they’re supposed to, never hear about other things, and hear about some things but reject them because they understand that the American mainstream thinks them icky. In other words, their thinking about the religious beliefs that they claim to be serious about tends to be pretty fuzzy.

These facts worry those conservatives who’ve paid attention to them. Last month, for example, one got CNN.com to publish an article warning parents that their teens may be “fake Christians,” adherents of “Moralistic Therapeutic Deism,” a term invented several years previous to describe the wishy-washiness (from the conservative point of view). Roughly, the complaint is that many self-described Christians think that all God really wants is for us to be happy nice people.

Most atheists will rejoice at these findings. If all religious believers in the U.S. dropped Biblical inerrancy, creationism, the belief that non-believers are damned, and screwy ideas about sex, PZ Myers might be able to call it a day. However, while Moralistic Therapeutic Deism may not not be as morally pernicious as many of the things Evangelicals believe, the worried conservatives who coined the term may be onto something.

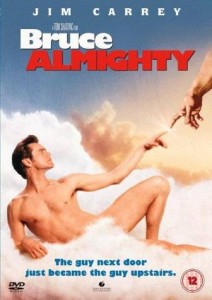

Consider the Bruce Almighty, the Jim Carrey movie that came out in 2003. Early in the movie, we see Carrey’s character (Bruce) bickering with his girlfriend over whether he’ll donate blood. Then he gets fired from his job as a news anchorman, and curses God. God (played by Morgan Freeman) appears to him and announces he’s giving Bruce all his power, with obvious ha-ha-you-won’t-be-able-to-do-better implications. Bruce uses this power to make his girlfriend’s boobs bigger, get re-hired as an anchorman, and land headline-grabbing stories. Then he decides he needs to be altruistic, so he answers everyone’s prayers. This results in a lottery jackpot having to be split so many different ways that each winner only gets a few dollars. There’s a break up, a near-death experience, a revelation that Bruce’s girlfriend just wants him to be a better person, and finally, a momentous decision by Bruce to help promote a blood drive.

On a moment’s reflection, it’s obvious that Bruce Almighty has a profoundly distorted set of values. It’s a world where a selfishness means wanting fame and a big-breasted girlfriend, where lacking these things is the worst misfortune that ever happens to anyone, and where being a good person means being the kind of guy that women who look like Jennifer Aniston would agree isn’t an asshole. It never occurs to Bruce to create for himself a tropical island filled with naked women, nor does he ever think “I’ll start off my good deeds with the cancer patients.” In other words, Bruce Almighty is a movie with a weirdly shrunken moral imagination.

Appallingly, while Bruce Almighty may not have been hailed as a master piece, some people still appear to have actually liked it. If memory serves, it was even used by my parents’ church as part of a “God in the movies” series. This suggests that many people see nothing wrong with a fairly obnoxious form of the “God just wants us to be happy nice people” view.

In a way this isn’t surprising. That people have obnoxious notions of what constitutes a nice person is old news, and the true cynic might claim to have expected that many people would never think to go beyond certain stereotyped behavior of the 21st-century U.S. middle class. The real puzzle is why people feel the need to bring God into it.

Perhaps due to reading too much Robin Hanson, my mind immediately leaps to a signaling explanation. Perhaps declaring a nebulous belief in God has been arbitrarily settled upon by some people as a way of signaling “I may be mainly interested in advancing my career, by I make token concessions to niceness like helping with blood drives!”

But explanations that don’t rely on the ideas of obscure economists aren’t hard to find. If you have a shrunken moral imagination to start with, I suppose it isn’t hard to worry that, unless people are told that God (played by Morgan Freeman) is on the side of niceness, people might fail to make important token concessions to that principle. I suspect that was the main thing going through the writers’ head when they wrote the script.

Also, invoking God is a good way to insulate yourself from mockery. It’s all too easy to mock ambiguously Buddhist hipsters for their ideas of what makes a good person. Once a person’s ideas of niceness are backed up by God, though, mockery is dangerous, because only vehement people would mock another person’s religious beliefs. Looking at it another way, we may frown on women who bitch to their friends about what an asshole their boyfriend is, but we are kinder to a woman that looks like Jennifer Aniston who kneels by her bed, praying to God for her boyfriend to be less of an asshole.

None of these attitudes are as pernicious are as pernicious as, say, religiously rationalized homophobia. But when we encounter the sort of attitudes expressed in Bruce Almighty, or other silly attitudes found among the fuzzier religious believers (like the narcissistic tendency to attribute every bit of good luck to God), we should still be willing to take the time to point and laugh.

if only bruce had taken part in a vaccination drive …

You’ve gotten an inaccurate impression of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism [MTD]. One of my colleagues in gender studies is a sociologist of religion; she’s writing her dissertation on MTD, including an ethnography of a local youth group whose theological views are basically MTD. As I understand her work, while MTD isn’t nearly as rigid as your standard fundamentalist (say), it provides a more substantial framework for doing ethics than `all God really wants is for us to be happy nice people’. The God-talk the participants adopt is relatively light on heady theological presuppositions, but it’s not entirely vapid. (Nor is it used as a rhetorical club to prevent mockery.) Probably more importantly, MTD gives its participants an extended but still fairly close-knit group of peers who can help think through ethical problems — whether or not one’s boyfriend is an asshole and whether or not to break up with him, for example.

In that respect it’s very much like many more traditional or more conservative religions. The nominal role of the Catholic priest may be to promulgate the Church’s dogma and lead the faithful, but his actual day-to-day activities make him more like a therapist, guidance counselor, or community organizer.

Dan,

I’d be curious to read some of your friend’s research, because ethnography would of course paint a clearer picture than my haphazardly gathered impressions. Still, I’m puzzled by your comment–everything I’ve heard until now about MTD has either explicitly described it as a bad thing, or been implicitly disparaging (at least to my ear). But maybe I’m reading my biases into the things I’ve read about it; I take it for granted that the sorts of benefits that are supposed to come from therapy don’t deserve a central place in any ethical system, but maybe this assumption was not on Christian Smith’s mind when he coined the term.

But maybe your point here is not defend the beliefs, but point to the value of youth groups where teenagers are able to discuss their personal problems with each other. I’m just not sure how strong the connection between that is, though, and the beliefs which Smith himself described as the God-as-therapist view.