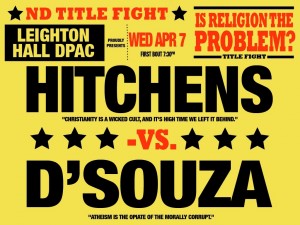

Overall, I’m very happy to have attended the debate. The amount of real interaction between Hitchens and D’Souza was far less than I was hoping for, in part due to the format of the debate. Still, Hitchens made for a very good representative of atheism, and actually I was pleasantly surprised by the approach he took.

Overall, I’m very happy to have attended the debate. The amount of real interaction between Hitchens and D’Souza was far less than I was hoping for, in part due to the format of the debate. Still, Hitchens made for a very good representative of atheism, and actually I was pleasantly surprised by the approach he took.

What I mean by that is this: mostly, I think of Hitchens as a polemicist, someone who’s very good at penning take downs of whomever he wants to target, a category that over the years has included Bill Clinton and Mother Teresa, anti-war protesters and Sara Palin. He’s also good with rapid fire comebacks, the kind of person you want appearing across from Bill O’Reilly or Sean Hannity on Fox. There’s another side to Hitchens though: the literary critic who takes the humanities very seriously while not taking post-modern nonsense too seriously. This is something I’ve noticed before. Though my review of god is not Great was mostly negative, I noted that Hitches has a “recognition, often lacking elsewhere, of the fact that religions tend to be more about ancient traditions than the modern reasonings often conscripted in their defense.”

That was the side Hitchens presented in the debate. He spoke first, and his opening speech sounded like what I imagine a early 20th-century Oxford literature professor would sound like, getting up to give a speech on religion, focusing largely on the place of religion in human cultural history. Hitchens said that religion was our first attempt to do a lot of things, but it would be odd to think that we should settle for that first attempt, it would be odd to think that, if there is a creator of the universe, he would have given his ultimate revelation to humanity to a few people at one point in history on a small stretch of desert. Religion, Hitchens said and went on to say repeatedly throughout the debate, looks like something manmade. He also talked about science a little, but it was obvious he was talking about it as a non-expert who very often could just refer you to what the experts were saying, and talked about science mainly for the sake of thinking about humanity’s place in the universe.

D’Souza treated the event much more as a traditional debate, which could have worked very well for him if he were a skilled debater, but D’Souza sounded a bit clownish, trying to hard to to be funny and smart without having much in either department. On the “trying to be funny side,” D’Souza started out with a quote from Winston Churchill about the Boer War, which was supposed to describe how he felt about Hitchens’ speech, to the effect of “it was so exciting to be shot at without any effect.” This got some laughs accompanied by a certain uncertainty at how to respond, then Hitchens gave a bit thumbs down, which got laughs and applause. That set the tone for most of the visible audience reaction to the debate: D’Souza said things obviously intended to get laughs, but Hitchens knew how to get more with less. Also, D’Souza didn’t really follow the Churchill quote up with much, I guess the point was he didn’t think Hitchens’ arguments were any good, but it wasn’t really clear.

On the smarts side, the most obvious annoyance coming from D’Souza is that he used lots of jargon that he seems to have made up himself, for example, claiming that science rests on presuppositional arguments, whatever that is.* After the Churchill joke, D’Souza’s opening speech ended up being dominated by a fairly standard list of things which atheists, allegedly, can’t explain. It could have been effective in the hands of a better debater, but it was easy to get the sense that D’Souza not only didn’t know much about what he was talking about, he also didn’t understand how out of his depth he was.

These opening speeches were fifteen minutes each, after that, Hitchens and D’Souza were supposed to get five minutes each to respond to each other. They both ran significantly over their allotted time, which was good, since five minutes is a ridiculously small amount of time to respond to a fifteen minute speech. Even so, they didn’t work as hard as they could have to seriously interact. The rebuttals made clear that Hitchens mainly wanted to talk about actual religions like Christianity and Islam, while D’Souza wanted to debate to be just whether there is some sort of God. I’m sympathetic to Hitchens here: I think he correctly perceives that the truth of particular alleged revelations is what most really serious believers really care about, and given that, it’s odd how unenthusiastic believers are about talking about those things in public. Still, it made for a less interesting event.

After the rebuttals was Q&A, which started off with the moderator, Mike Rea (who’s a philosophy professor), asking them one question each, and neither of them seemed to understand the questions. Oh well.

I was also disappointed that Hitchens never contradicted D’Souza’s claim that we must either believe that God created life, or a modern cell sprang into existence all at once by chance. This is scientifically ignorant, and someone who’s done as many debates on religion as Hitchens should be able to explain what’s wrong with common misconceptions like that.

On the other hand, there was one very good interaction in the Q&A when D’Souza claimed that Hitler was a secularist, Hitchens responded by quoting a place in Mein Kampf where Hitler claimed to be doing “the Lord’s work,” and D’Souza responded that Hitler faked belief in Christianity and really wanted to revive Teutonic paganism, and therefore was an example of secularism. Rather than belabor the silliness of blaming atheists for the actions of an apparent pagan, Hitchens thanked D’Souza for retracting his previous claim about Hitler, which was probably the right response.

That kind of interaction was rare, though. I suspect the quality of the interaction could have been improved considerably just by having three mircophones at the central table, rather than giving one mircophone to Rea and making Hitchens and D’Souza have to be at a podium in order to say anything. It probably made them feel like they had to make a speech in response to every question, instead of being able to have a conversation with each other.

Once it came time to end the debate, Rea suddenly declared that their response to the last question would double as their closing remarks. The question was about the meaning of life, and directed at D’Souza, which meant the last thing the would hear would be Hitchens talking about the meaning of life, and Hitchens made pretty good use of that fact. He said that the reason he does things like give blood and try to help Iranian dissidents is that he enjoys it, he enjoys knowing that he’s helping others, and enjoys meeting the people he meets pursing political causes. He rambled on a bit in these comments, and there was some awkward laughter when he used the word “pleasurable” to describe giving blood, but on the whole I think Hitchens managed to make a very good impression.

I know Hitchens leaves a lot of things to be desired, but I think he also does a lot of things well that few people who make a career writing and speaking about religion bother with. I think the video of the debate is scheduled to go up on the website for the Center for Philosophy of Religion, once it does and I find the time, I actually plan to study it to try to learn as much as I can from Hitchens’ performance.

*It pretty clearly wasn’t Calvinist presuppositionalist apologetics, even though I thought D’Souza might go there for a second.

claiming that science rests on presuppositional arguments, whatever that is

I’m a debate junkie (sadly), so I’ve heard DdS many times over. When he talks of science having presuppositions, I’m fairly sure he means “science presupposes that nature has regular laws that are discoverable. It’s only due to the Creator giving us regularity that we’re able to discover anything at all”

I think this is a terrible argument, but that’s by the by, and I’ll leave it to real philosophers to dig into why.

Obvious caveat: I haven’t listened to the debate in question, so treat this with a pinch of salt if it’s way off.

‘ D’Souza responded that Hitler faked belief in Christianity …’

If you want to embark on genocidal campaigns and agressive wars against Untermenschen, then you have to fake belief in Christianity.

You need to drive away the secularists, who will be put off by your faked belief in Christianity.

And you need to get onside the religious people who will support your genocidal campaigns of war, if you fake belief in Christianity.

@snafu: Actually, it sounded a bit like D’Souza was using “presuppositional” to mean “inference to the best explanation.” I’m pretty confident that that’s closer than your guess, having heard the debate. But D’Souza also sounded like me maybe thought he was saying something more profound than that.

Your summary confirms my dislike of D’Souza. There is something incredibly superficial about his attempts to connect with the crowd, and then the actual content of his arguments are so (1) overconfident and (2) narrowly informed that even the possibility for a genuine debate is limited.

Hitchens is in many respects my favorite atheist author. My primary reason is similar to the one you initially mention. I think Hitchens recognizes (1) the importance of the actual, live religions of people and (2) the cognitive and practical diversity of the religious life. Both facts force us to move beyond, say, mere arguments for the existence of God. Hitchens engages the whole narrative – history, philosophy, etc. – of the religions he confronts. Accordingly I find his interactions with Christians like Douglas Wilson to be the most fruitful.

I wouldn’t call Hitchens my favorite, but it’s good to know I’m not hallucinating his virtues.

I suppose I should clarify that I don’t think he has the best standalone arguments. That would probably be reserved for some academic, Quentin Smith or Michael Martin or Patrick Grimm or some such person.

Without an explanation by D’Souza himself, it is difficult to determine how he is using the word presuppositional. But when this word is used by someone who espouses “Calvinist presuppositional apologetics”, it is most often meant to be a philosophical critique on the neutrality or preeminence of science versus religion. This position claims to point out that any consistent intellectual system rests on assumptions (presuppositions) which cannot themselves be proven within the context of the system itself. Everyone inevitably “brings his assumptions with him” when as he reasons. So, making this argument is an effort to put all systems of thought on the same footing … i.e. both science and religion have faith, at least in a foundational way, so stop pretending like you’re better than me! If we accept this position, the most that can be said of a proof, or of truth, is that it has the quality of “internal coherance”. Part of the act of thinking philosophically then becomes an effort to uncover your presuppositions and come to grips with them … to be at peace with your personal “web of belief”. But someone with common sense’ is about to interrupt me and say, “The edifice of science actually WORKS (by its own internal standards), therefore the underlying assumptions must be correct”. But, don’t be surprised when another person wants equal time to say, “The edifice of religion actually WORKS (by its own internal standards), therefore the underlying assumptions must be correct”. If the presuppositional argument is made in detail, it is most likely to be an effort to pull the rug out from under anyone who would argue that science should have precedance over religion as a foundational philosophy or worldview. Curiously, the same argument is not employed the other way around by atheists. Why? At this time in history, science is often assumed to hold the position of ‘neutrality’ in an argument about ‘facts’. Religion therefore has to use the presuppositionalist argument to pull the plank out from under the person who presumes himself to be uniquely qualified to determine the truth. And don’t think I’m talking about truth in the sense that the moon is ‘n’ kilometers from earth right now … or mama’s cake mix should be made with 2 eggs, not 3 … no, I’m talking about interesting (i.e. hard) questions, like whether god was ever involved with the creation of the universe or of life, or whether we should be doing stem cell research, etc. Ok ok, I’m going to have to admit it sooner or later … so here goes. From a philosophical and worldview point of view, I think the presuppositional argument might be correct … maybe even definately correct … to me it is relentless in its logic. We all do make assumptions or presuppositions that we can’t prove. But actually that’s ok by me … all is not lost. “As for me and my house”, I choose to root my faith in secular presuppositions. I choose not to let my faith be informed by any religious document. I am an ‘agnostic presuppositionalist’, so I should try to make the pluralistic society in which I live more consistently pluralistic – to include all points of view in the public debate … right? But, when the school board’s budget can only buy one astronomy book, with one point of view, I’m not going to be happy with the one that says without god there couldn’t have been a big bang. Or the biology book that says without god’s intervention life never would have begun. Why? Because my worldview doesn’t have those planks of faith in it. What I really think is that worldviews are equal in many foundational respects, but they are not reconcilable. As they interact over time, some will win and others will lose. I want mine to win. I admit, this makes my intellectual arguments resemble feral animals with claws more than angels with wings. Oh well, so be it. Let the fight begin.